|

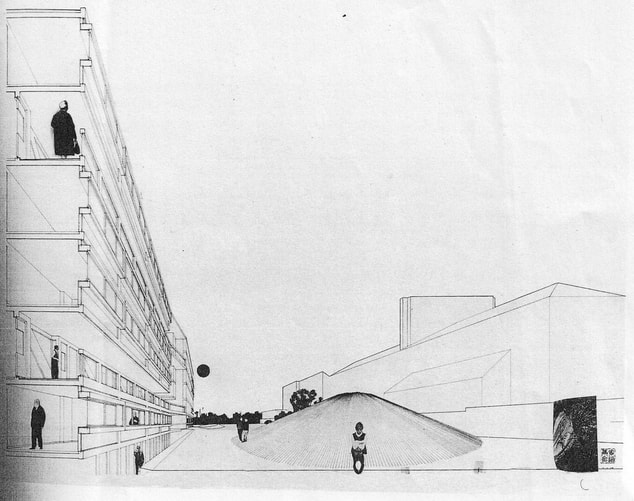

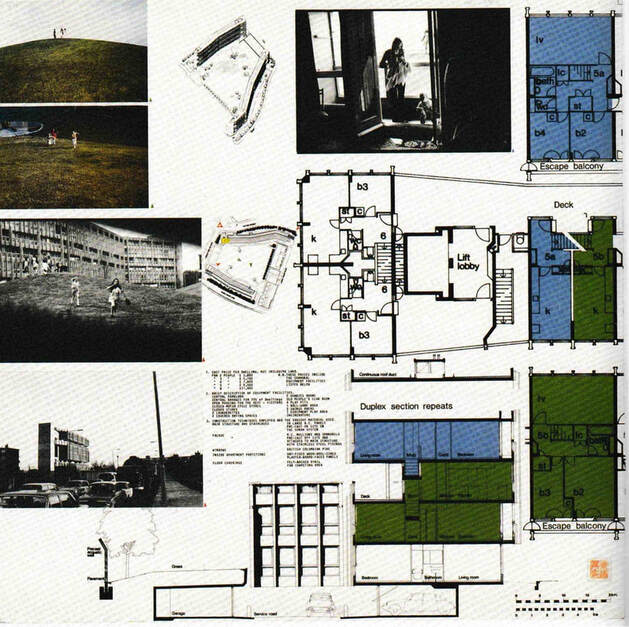

For 50 years the Robin Hood Gardens estate in Poplar has drawn praise, criticism, derision and scrutiny, much like its designers, Alison and Peter Smithson, did in their lifetime. As the last remnants of the estate are demolished we look back at how and why this divisive monument to modernism was built, and why it will soon vanish. The estate was commissioned by the Greater London Council, a prodigious builder of new housing since 1945, when it was the London County Council. The inhouse architects departments of these two organisations designed the lion's share of the capital's new estates, but outside architects were often commissioned to design municipal projects, most notably Erno Goldfinger whose Balfron Tower is just a stone's throw away from Robin Hood Gardens. The Smithsons came to fame with their design for Hunstanton School in Norfolk (1954), a pared down retort to the Scandinavian flavoured modernism of postwar British architecture. The next 15 years saw more column inches than completed projects, with their largest building being the Economist Offices (1965) in St James Street. The idea for an estate in the area had first been proposed in 1963 on what was then Manisty Street, home to the 19th century Grosvenor flats, built as part of previous slum clearance effort. The site was later expanded with Robin Hood Lane as its eastern boundary from which the estate would take its name. Over the next few years the site and brief were altered until a plan for 214 homes housing 700 people in two long slab blocks running parallel to the Blackwall Tunnel approach road were confirmed. In between these two slabs would be a green area, a ‘stress free’ area protected from the chaos of city life by buildings of the estate. In the middle of this area a mound was created using construction debris, creating a focal point for the space and a feature for the estate's children. An important part of the design of the estate were the block’s ‘streets in the air’, external access decks that the Smithsons hoped would become inhabited and used just like the terraces of neighbouring streets. This idea was first introduced by the Smithsons for their Golden Lane Estate competition entry in 1952, eventually won by Chamberlin, Powell & Bon. The depth of the walkways were to be sufficient so “Two women with prams can stop and talk without blocking the flow..”, and children would be able to play outside of their flats. Alongside the Smithsons, the recently deceased Christopher Woodward and Ken Baker helped design the project. The flats were arranged so the living areas and kitchen/dining rooms were largely facing away from the main road and towards the garden area. All flats, except for those for the elderly on the first floor, were on two levels with the bedroom placed either above or below the entrance floor. The exterior of the two blocks featured modulated concrete facades, another attempt to deflect noise from the busy parallel road. The Smithsons had approached the design of the estate in typically unconventional style. They researched the area's history back to the start of the 18th century, taking interest in the trades, residents and buildings that made up the neighbourhood. They also took brass rubbings of old street plaques, produced photomontages and even a mosaic made up of shards of china originally used as ballast by ships in the nearby docks. The materials used for the construction of the estate were unapologetically brutalist, with the blocks formed by a mixture of insitu and prefabricated concrete, overseen by engineering consultants Ove Arup & Partners. The systems part of the construction employed the Sundh slab method, developed by Swedish engineer Ernst Sundh, with the contractors Walter Lawrence & Son responsible for this and the construction of the whole site. The estate was completed at the point at which the tide started to go out for large, systems built concrete housing schemes. Architectural, social and financial opinion had turned against them in favour of smaller projects, largely made up of houses in brick with pitched roofs, as seen with the later Thamesmead phases. Vandalism was a problem from the start on the estate. The four outside play areas were damaged soon after opening and left unrepaired. The Smithsons were slightly bewildered at this violence against their design, seeing it as a reaction against consumer society rather than their buildings. This violence was matched by the local authorities' indifference to the upkeep of the estate. As seen elsewhere, the estate and its buildings were left to deteriorate until deemed not fit for use. Tower Hamlets drew up plans to demolish Robin Hood Gardens in 2008, as part of the regeneration of the Blackwall Reach area. Preservation campaigners and architects condemned the plans and launched a campaign to save it. Listing was turned down by English Heritage and a Certificate of Immunity was issued, barring any listing for 5 years. Another attempt at listing was made after this time had elapsed but was again turned down. The block on the western side of the site was demolished in 2017. The Victoria and Albert Museum salvaged a three storey section and other parts of the estate, but they have not yet been put on display. The remaining parts of the estate were cleared in 2022, the end to 50 years of Robin Hood Gardens. References

Alison and Peter Smithson (Works and Projects)- Marco Vidotto Alison and Peter Smithson (Twentieth Century Architects)- Mark Crinson Buildings of England: London East

0 Comments

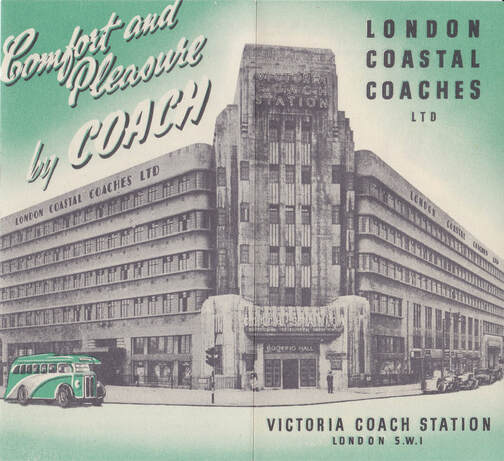

We are delighted to introduce a guest blog by Peter Wyeth, celebrating 90 years of Victoria Coach Station.... Belgravia today seems a most unlikely location for a major coach station, but in 1930 it was the perfect location, virtually opposite the railway terminus. An earlier coach station had outgrown itself by the 1920s and the 1 & 3/4 acre site was purchased on 2nd September 1930. The architect Thomas Wallis, who had designed the famous Firestone art-deco factory on the Great West Road, produced a design for a 400 foot long building. Ninety years on it is worth realising what a great leap forward the Victoria building was. The modern image of the new coach station gave an immense boost to the image and respectability of the rapidly developing industry. The Coastal Coach Company Ltd, who commissioned the design, really only needed the ground and first floors, but the decision to add three floors above transformed it into a statement on the street to exceed the nearby Victorian eponymous railway terminus. Early plans for a hotel were replaced by office accommodation, christened Coastal Chambers. If the steam train was a creature of the nineteenth century, the coach belonged firmly to the twentieth. The sleek, art-deco exterior was only part of the story. Architect Wallis’s father was a bricklayer and his son was passionate about creating good working conditions for staff. His detailed attention to lighting, heating and ventilation was ahead of its time, and the bright and airy offices above the accommodation for 150 coaches and a 62 line telephone exchange were soon let, despite the crash of 1929. On 10th March 1932, the opening ceremony was conducted by the then Minister of Transport, with the unbelievable name of John Pybus, and attended by 250 guests. The contrast between top-hat and tails, the period bus and the modern building behind is striking.The same day saw the inauguration of the London to Glasgow night bus, a fourteen hour journey, powered by a diesel engine; another first as, hitherto, all long-distance coaches were petrol-powered. The building received national and international acclaim for its design and concept. Along Buckingham Palace Road were shops at ground level, including a tobacconist with a hairdressing salon above it on a mezzanine floor. Along Elizabeth Street are a newsagents, a quick-service bar and buffet bar, and above, on a mezzanine floor, a lounge bar. The executive offices and oak-panelled boardroom were located on the first floor, above the main entrance. On the first floor was a large 200 seat restaurant with a dance floor and extensive kitchens. The restaurant was painted in the very 30s colour scheme of pale green and pink with a gold spray, and the excellent dance floor was a particular attraction. Coastal staff had their own restaurant where they could get a square meal for one shilling (5p), and a staff recreation room at the top of the building. As eating habits changed, by the late 60s the restaurant finally closed. The glory days of the 1930s were long gone, but the art-deco exterior remains a cheerful reminder. Peter Wyeth is a film-maker, a runner-up for the Grierson Award: 'Twelve Views of Kensal House (After Hokusai)', plus a TCM drama Award: 'Pane'. Author of The Matter of Vision (2015), and a writer on Architecture & Design (26 articles for The Modernist). He is developing a documentary on the discovery of a Roman Road in Wales: Stradland. His latest book, The Lost Architecture of Jean Welz is published on 11th August https://www.waterstones.com/book/the-lost-architecture-of-jean-welz/peter-wyeth/9781954600003

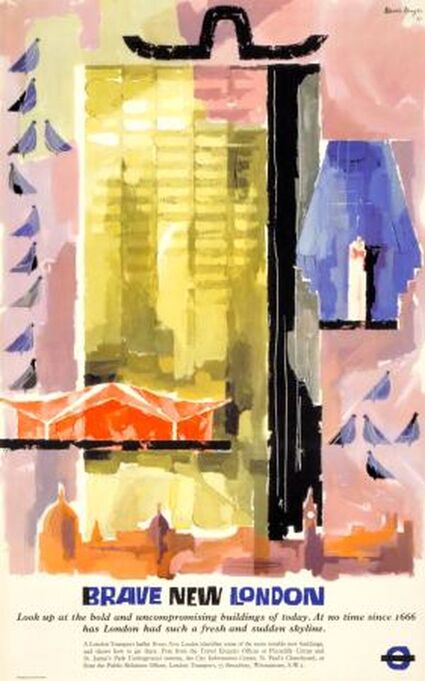

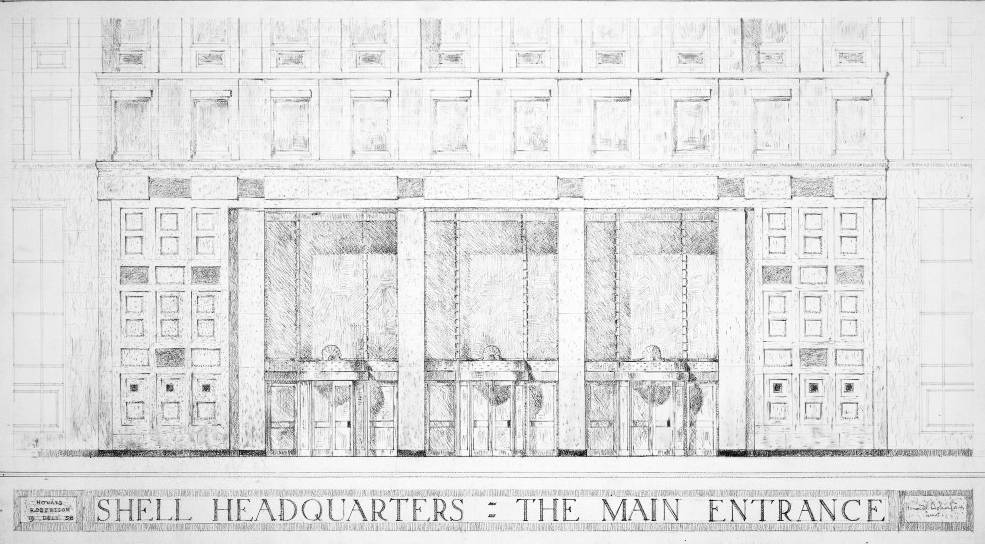

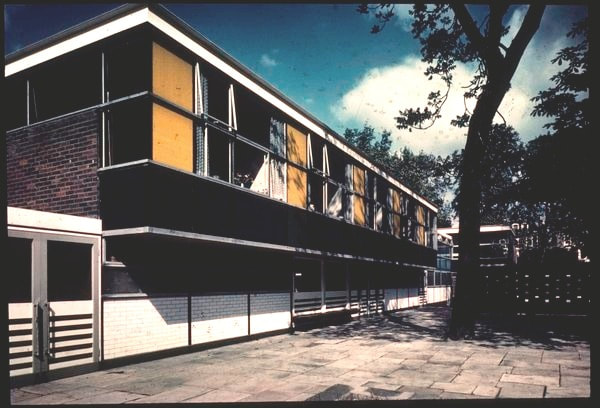

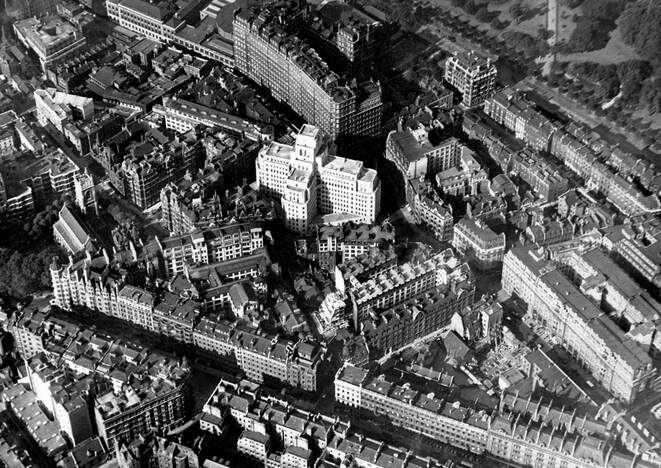

This article was first published by the Belgravia Society and is kindly reproduced here with their permission. To find out more about the society, visit their website here https://www.thebelgraviasociety.com/ “Look up at the bold and uncompromising buildings of today. At no time since 1666 has London had such a fresh and sudden skyline” We have previously looked at the postwar rebuilding of Bethnal Green and White City, seeing how those areas rose from the literal ashes. We now turn to look at the centre of the capital and how the city remade itself into Brave New London. In 1960 London Transport issued a leaflet and poster highlighting the new architecture springing up across the capital. They were both designed by artist Hans Unger, who would later design some of the Victoria Line tilework, (read more on his life here). The leaflet listed a number of buildings recently completed across the city from the Alton Estate in the west to Span estates in Blackheath in the east. Of the 24 buildings listed in the leaflet, 5 have been demolished outright and a couple more have been refurbished. The remaining buildings are intact and largely listed. Some of the buildings featured are still considered classics of their time, whilst others have slipped into obscurity. We will examine all of them here. Starting with the demolished buildings, the two headliners are Owen Williams’ Daily Mirror building and the Peter Robinson store by Denys Lasdun. The Daily Mirror building at Holborn Circus was built between 1955-61, providing a new headquarters for the newspaper. It was the last building Willaims was involved with before retiring, with the firm of Anderson, Forster & Wilcox designing the exterior and interior finishes. The building was deemed surplus to requirement in 1994, when the paper moved to Canary Wharf and was demolished. The Peter Robinson building (1957-9) was a five storey department store on Strand, with an exterior palette of glass, stone and bronze. The ground and first floor were the sales floors, with the top three floors consisting of offices. The building was demolished in 1996. The other demolished buildings are; Bucklersbury House on Cannon Street by Owen Campbell-Jones offices demolished in 2010, Moor House on London Wall another office building, this time replaced by a Terry Farrell design, State House on High Holborn by Trehearne & Norman and Quintin School in St John’s Wood by Edward D. Mills & Partners, demolished in 2014 for a Van Heyningen and Haward design. The refurbished projects include Eastbourne Terrace (1958) in Paddington by C.H. Elsom & Partners, an office complex refurbished by Stiff & Trevillion in 2016. Thorn House on Upper St Martin’s Lane by Basil Spence has also been given a makeover. The 15 storey building was opened in 1959 for Thorn Electrical Industries and featured an eight foot high exterior sculpture by Geoffrey Clarke. The building was refurbished in 1990 by Renton Howard Wood Levin, the partnership founded by the building's original job architect for Spence, Andrew Renton. The remaining, existing buildings are largely housing estates with a few schools and offices included. The most famous schemes on the list are the Alton Estate in Roehampton and the Golden Lane Estate in the City, now both icons of early postwar modernism. Lesser heralded estates include Highbury Quadrant (LCC, 1954), Lansbury (L.C.C, 1951) Sceaux Gardens (1959) and Munster Square (Frederick Gibberd, 1951). Aside from Sceaux Gardens, designed by the architects department of Camberwell Metropolitan Borough Council in a typically Corbusian style, the other estates showcase a Scandinavian influence, which was more widespread in the early postwar period. This schism was laid bare at the aforementioned Alton Estate, when the two competing factions of the LCC housing department faced off across the slopes of Roehampton. The eastern section was designed by a team under Rosemary Stjernstedt in the Scandinavian idiom, with the western sector designed in what would become the dominant New Brutalist style of the 1960s. This team for this section was made up by the future founders of Howell Killick Partridge & Amis, as well as Roy Stout later of Stout & Litchfield. Two Span estates are also included on the list, Parkleys (1956) at Ham Common and The Hall and Corner Green (1957-9) in Blackheath. Span Developments was founded by Geoffrey Townsend in 1956 to create speculative, modern estates influenced by Scandinavian design. Houses were usually flat roofed, two storeys high and arranged in terraces. Apartment buildings were usually no more than four storeys with open plan interiors. The company's estates, designed by Eric Lyons & Partners, became very popular with new schemes being built all over London’s suburbs and the Home Counties. Parkleys is one of the best known of Span’s estates, with the housing spread around mature trees and hedges, allowing the estate to flow and be part of its neighbourhood. Another Lyons project featured in Brave New London was his housing for the Soviet Trade Delegation in Highgate (1957), which includes a four storey apartment block in exposed concrete and brick with a nursery and an assembly hall. Away from housing there are four office blocks in the guide. Congress House on Great Russell St was designed by David du Reiu Aberdeen for the Trade Union Congress, opening in 1957. Aberdeen had won the competition for the building in 1948 with his design featuring large areas of glass on the ground floor, a granite and blue tile exterior and an inner courtyard with a war memorial by Jacob Epstein. The building was refurbished between 1996 and 2019 by Hugh Broughton Architects, upgrading facilities and restoring original materials. Castrol House on the Marylebone Road (now Marathon House) was completed in 1959 as offices for the oil company. It was designed by Gollins Melvin Ward & Partners, and was one of the first American style post war skyscrapers in the country. The building is arranged in the slab and podium manner, with a 16 storey tower next to a lower podium block, and a glass curtain wall finish. The building has now been converted to apartments with the curtain walling curtailed to allow domestic occupation. The other two commercial buildings are the Sandersons offices and showrooms and the Shell Building on the South Bank. Sanderson House (1960) in Berners Street was designed by Reginald Uren of Slater, Moberley and Uren, with a glass curtain wall as at Castrol House and a courtyard garden. The building's most interesting feature is the stained glass panels by John Piper. Sanderson House was listed in 1991 and turned into a hotel in 2001. The Shell Building (1960) was designed by Howard Robertson as headquarters for the Shell oil corporation. It was built on the site of the recently cleared Festival of Britain and was criticised for its dull design, being finished in Portland stone rather than concrete or glass. The building was arranged in two sections, an “Upstream” building and a “Downstream” building. The upstream building was a 27 storey tower with adjoining 9 storey wings (the wings have been demolished). The downstream building, separated from the tower by the railway, is a 10 storey L-shaped block with a curved range, now converted into apartments. The last couple of buildings on the list are designed for the younger generation of the time. Bousfield School (1956) in Chelsea was designed by the partnership of Chamberlin, Powell & Bon, known for the designs of Golden Lane and Barbican estates. The school features curtain walling with coloured panels and a spherical concrete water tower in the grounds. Holland Park School was designed by D. Rogers Stark of the LCC, to house 2000 pupils on a site that was formerly part of the Georgian era Phillimore estate. The school buildings were arranged in long ranges of four storeys, built in dark brick with glazed stair towers. The 1950s building was demolished at the start of this century, with a new school building opened in 2012. Holland Park Youth Hostel is included along with the school. The hostel was opened in 1959, designed by Hugh Casson and Neville Conder on the site of Holland Park house, partially destroyed by Luftwaffe bombing. The final building on the list is Gardiner’s Corner, which seems to have been a department store at the junctions of Chapel Street and Edgware Road, probably where the current Tigris House is. The leaflet showcases a rising new metropolis, with bombsites and grimy Victorian buildings supplanted by high rise structures of concrete, steel and glass. Of course this transformation did not meet with universal acclaim, with many observers worrying that Old London would be replaced by mini Manhattan. The London Transport Board would continue to boast of the capital's new architecture with the publication of Modern Buildings in London by Ian Nairn in 1964, a slim but thorough roundup of modernist buildings on the extended transport network from the 1930s to the mid 1960s. As we have seen, much of what is “Brave New”, quickly becomes “Feeble Old” and disappears for something more up to date. But in buildings like the Alton Estate, Golden Lane, Bousfield School and others we can still see a glimpse of the future as seen from 1960.

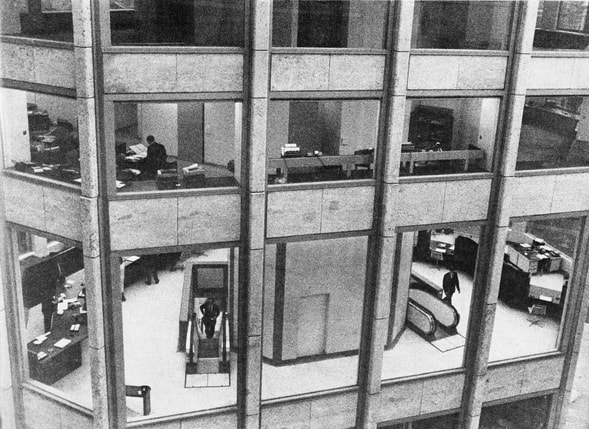

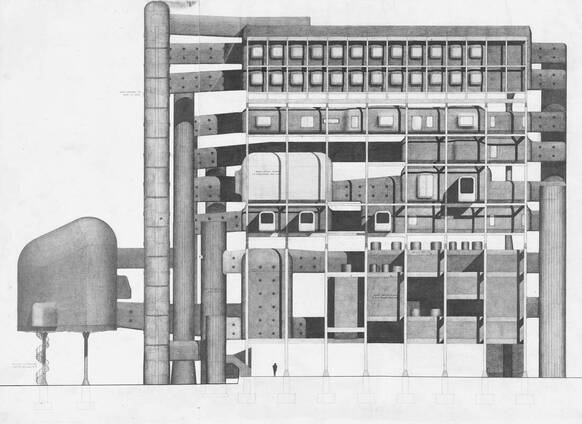

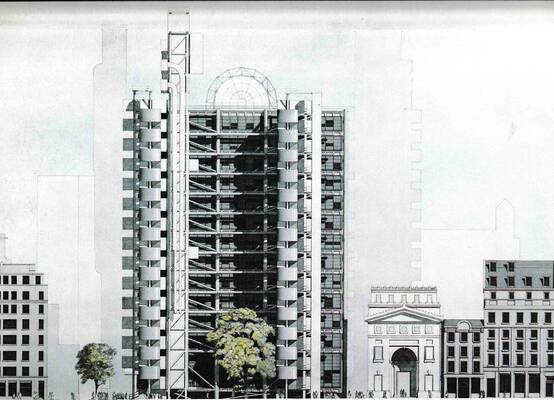

The Lloyd’s Building in Lime Street was officially opened on 18th November 1986 by Queen Elizabeth II. Designed by Richard Rogers and Partners, the radical inside out plan is the epitome of the High Tech drive to maximise a buildings usable space by separating services from the purpose of the building. Air conditioning ducts, electrical conduits, water pipes and lifts are all placed on the outside of the structure, allowing maximum floor space for the insurance brokers and agents of Lloyd’s. In the 35 years since its completion the building has been widely praised, becoming one of the few post war buildings to be granted Grade I listing. Lloyd’s of London had originally been based in the 1928 building at 12 Leadenhall by Edwin Cooper, before moving in 1958 to a new building across the road at 51 Lime Street. The 1928 building was incorporated into the Rogers structure, as was the Committee, or Adam Room, an 18th century dining room by Robert Adam that had been part of the 1950s building. Rogers design emanates from the ideas of Bowellism, formulated in the late 1950s and early 1960s, by the founders of Archigram, particularly Michael Webb, whose project for a headquarters for the Furniture Manufacturers Association in High Wycombe featured precast concrete cells inserted into place on a skeleton frame with ducts and pipes carrying utilities were needed. Rogers used these ideas in his Pompidou Centre in Paris, designed with Renzo Piano, which opened in 1977. The structure featured colour coded utilities on the exterior (green for plumbing, yellow for power cables, etc), freeing up the exhibition space inside. Rogers and Piano had won the competition to design the building against a wide field of the world's architects. The construction took 6 years, and the completed building was met with puzzlement and sometimes outright hostility. However the impact of the building was felt far and wide, with cultural and financial institutions looking for eye-catching, iconoclastic designs for their new buildings. The Lloyd’s building consists of six towers, (three of which carry services) around a rectangular space. The removal of the services from the internal space allows each floor to be flexibly planned and easily changed according to the company's needs. The interior is lit by an atrium with a glass barreled roof, with the Underwriting Room at the centre of the building. Eva Jirinca designed the Captain's Room restaurant, using fabrics arranged to evoke the billowing of a ship's sails, in recognition of Lloyds’ nautical roots. Jirinca’s designs were removed in 2000. The building was bought by the Chinese insurance company Ping An in 2019, and there are plans to redesign the interior of the building to account for the post pandemic, digital age.

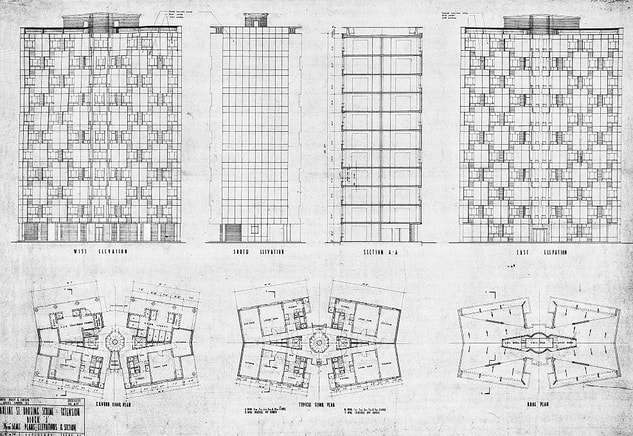

Like many municipal authorities in London immediately after World War II, the highest priority of the Metropolitan Borough of Bethnal Green was to rehouse those whose homes had been destroyed in the previous 6 years. Over 5000 people were living in temporary homes in 1946, many prefabricated structures, with the last of these still to be housed 20 years later. A mass house building programme was launched all over Britain, but especially in the east of London. This led to Bethnal Green commissioning some of the most interesting and radical designs for mass housing in Britain. Architects both storied, such as Berthold Lubetkin, and emerging, like Denys Lasdun, designed estates to house those made destitute by the war and to look forward to a brave new world. The first estates to be completed in Bethnal Green after the war were those that had already been designed before the war by the London County Council Architects Department. The Minerva Estate opened in 1946 with accommodation for 1000 people, and was built in reinforced concrete. The first estate to be designed and built in Bethnal Green post war was the Park View Estate by De Metz and Berks for the L.C.C., which opened in 1951, with 267 flats. The most interesting part of the estate is the community centre, now known as the Glasshouse, with its scalloped concrete roofline, and cantilevered first floor. Building continued through the 1950s with a succession of estates designed by a combination of the L.C.C., Bethnal Green’s surveyors department and private firms. These estates were solid but unspectacular designs, but by the end of the decade a number of schemes would turn the attention of the architectural world towards the borough. Berthold Lubetkin had been one of the preeminent modernist architects of the 1930s in Britain, producing designs such as the Penguin Pool at London Zoo, the Highpoint Flats in Highgate and Finsbury Health centre, all high points in the decades architecture. The post war years saw the dissolution of his Tecton practice and a new partnership with Francis Skinner and Douglas Bailey. After the completion of the three estates delayed by the war in Finsbury (Spa Green, Priory Green and Bevin Court) the trio designed three more estates for Bethnal Green. The first to be opened was the Dorset Estate in 1957. It is situated between Hackney Road and Columbia Road, and featured 8 housing blocks in its original plan (all named after the Tolpuddle Martyrs), with the most eye-catching being the two Y-shaped blocks of George Loveless and James Hamnett houses. The blocks feature the patterned facades in concrete that would become the partnership's trademark in the post war years. The estate also features a circular library and community centre and a pub, originally called The Royal Victoria. The 20 storey Sivill House point block was added in 1966, six years after Lubetkin's retirement but he had provided designs for the tower in the late 1950s. A year after The Dorset Estate opened, the Lakeview Estate was completed next to the old Hertford Union canal. It is on a much smaller scale than the Dorset estate, but the materials and design make it instantly recognisable as a Skinner, Bailey & Lubetkin scheme. The main focal point of the state is the 11 storey apartment block, with its geometrically patterned facade. There are also four 2 storey old peoples homes in the grounds facing onto the canal. The estate was built by the borough's own direct labour force. The third estate for the borough by Skinner, Bailey & Lubetkin is Cranbrook, between the Old Ford and Roman Roads. Opened in 1964, the estate is set around Mace Street, a figure of 8 road, with the 6 tower blocks, 5 smaller terraces and bungalows, all arranged in a stepped sequence to allow maximum sunlight throughout the day. The blocks themselves are constructed of concrete and faced with grey brick, with the tower blocks enlivened by bright green concrete struts and tiles. The grounds were designed to give a trompe l'oeil view of Victoria Park (now blocked by a neighbouring development) and also feature Elisabeth Frink’s “The Blind Beggar and his Dog” sculpture. Just a little to the south, the second phase of the Greenways Estate by Yorke, Mardall & Rosenberg was opened in 1959. The first part had been designed by Donald Hamilton, Wakeford & Partners, opening in 1951. The new section by Yorke, Mardall & Rosenberg added a series of five storey blocks, constructed of reinforced concrete, faced in precast panels with stone chippings. Shops or lock ups were situated on the ground floor of each block. Next to the Greenways estate are two blocks that left behind the rectangular form of most apartment schemes of the era, in favour of something more daring. Sulkin House and Trevelyan House were designed by Denys Lasdun, then with Fry, Drew, Drake & Lasdun, and completed in 1959. The two cluster blocks are eight storeys in height, with maisonettes angled around a central service tower. This design produced a high density housing scheme with minimal disruption to the existing street plan and reduced demolition. Lasdun also designed the more regular flanking four storey blocks as part of the scheme, recognizable as Lasdun projects due to their bold concrete staircases. The cluster block design was repeated by Lasdun at another scheme, Keeling House in Claredale Street (1960). Here the scale is much larger, 16 storeys instead of 8, with 56 two storey maisonettes and 8 studio flats arranged in 4 towers around the service core. The effect on the streetscape is (or maybe was) more pronounced than at Usk Street, with Keeling House rising dramatically out of the surrounding streets of terraced houses. A lower rise block, Bradley House was also built as part of the estate, but this was demolished in 2005. Keeling House was sold by Tower Hamlets Borough in 1999 and turned into private apartments, with a glass foyer added at ground level, as well as eight penthouse flats on the top service floor. A couple of other noteworthy projects were completed by the Municipal Borough of Bethnal Green, before it was subsumed into Tower Hamlets in 1965. St Peter’s Avenue is just west of Keeling House, and the new estate there was built between 1964-7. It features 5 six storey blocks containing 174 dwellings, constructed of concrete with brick infill and bold concrete balconies and ventilation towers. On Cambridge Heath Road is Mayfield House, opened in 1964 as a mixed residential and work scheme, with flats, shop units and striking gallery at one end. There are 54 flats in a six storey block, which was designed by the partnership of Kenneth Wakeford, Jerram and Harris to include facilities such as a music library and recital hall in the building. Unfortunately the glass clad gallery has been boarded up since 2014, with various campaigns since to reinstate the windows.

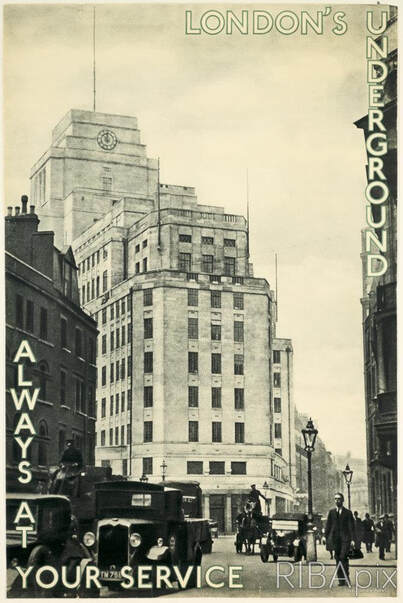

The Metropolitan Borough of Bethnal Green became part of the new London Borough of Tower Hamlets in 1965. In the 20 years from the end of World War II to its abolition, the borough had built over 1500 dwellings, helping to rehouse much of the thousand of people made homeless by the war. The rebuilding effort also saw the standard of dwelling raised, away from the cramped Victorian terraces and tenements, towards a (brief) brave new world. 55 Broadway was officially opened on 1st December 1929. Designed by Charles Holden as the new headquarters for the London Transport Board, it replaced the previous hodge podge of buildings the board used in the same area. The new building brought together different departments under one roof, allowing faster communication and creating a corporate atmosphere. As well uniting the company under one roof, the building would also contain St James Park tube station. Holden, and his firm, Adams, Holden & Pearson, were appointed to the design in 1925, after an initial plan by Sir A.E. Richardson was rejected by LTB director Frank Pick for being too old fashioned. The site chosen for the building was an awkward, asymmetrical plot, hemmed in by other buildings. To counteract these problems, Holden arranged the building in an irregular cruciform plan, with a long east-west axis and a shorter north-south one. The upper floors step up, getting smaller in floor area as it gets to the top. This allows natural light into each office, as well as allowing more light down to street level. The services such as lifts and ventilation were built into the central tower core. Holden had previously specialized in the design of hospitals when he joined the firm of Henry Percy Adams (later to become Adams, Holden & Pearson) at the start of the 1900’s. This experience was to provide useful in creating the large, integrated design of 55 Broadway. Another influence on the design was that of the fifteen-storey General Motors Building in Detroit (1919-22) by Albert Khan, also designed to allow sunlight and air to each of the buildings numerous offices. 55 Broadway is constructed around a steel frame encased in concrete and then clad in stone. Portland Stone, a material Holden had used on a smaller scale for London Transport in his Northern Line Extension stations a few years earlier, was used from the 3rd floor upwards, with blue-green Norwegian granite for the first and second floor. Inside, flooring of Travertine limestone forms three paved public arcades and covers the staircases, with bronze used for the railings. Each floor contains a drinking fountain and an automatic mail chute, details picked up from American office designs of the time. The exterior of the building was decorated with a range of sculptures, produced by a number of different artists. Reliefs depicting “The Four Winds” were sculpted by Eric Gill, Henry Moore, Alfred Gerrard, Eric Aumoinier and Sam Rabinowitcz. Jacob Epstein, who Holden had previously worked with on the British Medical Association building on The Strand and Oscar Wilde’s tomb in Paris, designed two sculptures, Day and Night, which proved controversial. Day in particular drew heavy criticism, with a campaign started to have it removed. Pick, despite his initial reservations to employing Epstein, offered to resign to loyalty to Holden, but it was refused. Eventually 1.5 inches was removed from the statue to appease the complainers. When it opened, 55 Broadway was, at 176 ft the tallest building in London. The top 4 floors were kept unoccupied, as they were above the limit decreed by the 1894 London Buildings Act. The Observer newspaper called it “The Cathedral of Modernity”, and it was widely praised as the harbinger of English Modernism, balancing Arts and Crafts detailing with new building technology and American design.

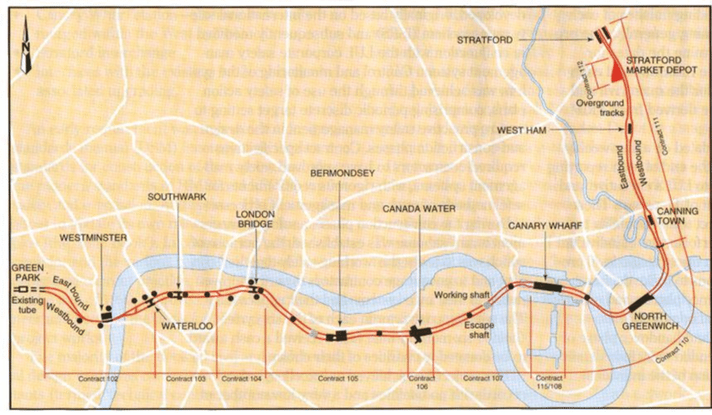

It has served as the headquarters of the London Transport and then TFL for 90 years, but that time is drawing to a close. A 2015 plan by Tate Hindle to convert the building to flats and offices came to nothing, and in September this year TFL agreed a deal to sell the property to the Integrity International Group, who have not yet announced their plans for the building. 55 Broadway was Grade I listed in 2011, and so whatever its future, the building should stand as a marker of the journey of British architecture from Art and Crafts towards Modernism. References Charles Holden: Architect by Eitan Karol Bright Underground Spaces by David Lawrence Buildings of England: London 6 City of Westminster by Nikolaus Pevsner and Simon Bradley The Jubilee Line is celebrating two anniversaries this year. First of all, it is 40 years since the line first opened, connecting Stanmore to Green Park. The second anniversary is that of the 1999 Extension, which extended the line from Westminster to Stratford. Not only did the line extend through the heart of the capital, into the newly built Canary Wharf and East London, but it also created a sequence of spectacular stations in the process. The Jubilee Line Extension stations; Westminster, Waterloo, Southwark, London Bridge, Bermondsey, Canada Water, Canary Wharf, North Greenwich, Canning Town, West Ham and Stratford; became the most feted since the heyday of Charles Holden in the early 1930’s. Originally to have been called the Fleet Line, and to extend down to Lewisham, the Jubilee Line opened on 1st May 1979. The stations that made up the line were older stations inherited from other lines, such as the Bakerloo, whose services it replaced from Baker Street to Stanmore. Various extensions were planned over the next 20 years including through Surrey Docks and south to New Cross, and east through the former docklands (which would eventually happen as the Docklands Light Railway). A 1980s study group recommended extending the line through Westminster and on towards Stratford. This idea was given the go ahead in 1990 and construction began in December 1993, with a projected finish date of mid-1998. The new line eventually opened in stages between May and December 1999, with the eastern stations of North Greenwich, Canning Town, West Ham and Stratford coming into service on May 14. The design of the 11 stations was overseen by Roland Paoletti, the British-Italian architect previously responsible for designing stations on Hong Kong’s Mass Transit Railway. Paoletti used a group of architects to design the stations, giving each practice one or two stations. The architects he chose, include some of the most famous in contemporary architecture; Foster + Partners, Michael Hopkins Architects and Alsop Lyall & Stormer; as well as practices who were lesser known at the time. Despite the diverse group of architects, the finished stations have a common design philosophy, and are recognizably part of the same line, something Charles Holden and Frank Pick achieved with their Piccadilly Line stations in the 1930’s. The first station on the extension, Westminster, is also one of the most spectacular. Designed by Michael Hopkins Architects, the new station was built below Portcullis House, also designed by Hopkins. The station is made up of a vertical space, 128 feet deep. The concrete structural support columns, escalators and stairs are all left exposed, giving the space a dramatic, futuristic feel. At Southwark, designed by Richard McCormac of MJP Architects, the ticket hall has a 40 metre high wall in blue glass, designed by artist Alexander Beleschenko. Bermondsey designed by Ian Ritchie Architects has, like Westminster, a void down to the platform area, drawing in light from street level. The design of Canada Water harks back to the era of Charles Holden stations like Arnos Grove and Chiswick Park, with its drum shaped ticket hall in glass, again allowing light down to the platform area. It was jointly designed by Ron Herron Associates, Bruno Happold and the Jubilee Line Extension Project architects. Next door is an integrated bus station (another throwback to the days of Holden and Frank Pick), designed by Eva Jiricna. Next along the line is Canary Wharf by Foster + Partners. The station is situated in a space 78 feet deep by 869 feet long, with once again light being directed to the platform areas via two curved canopies at either end of the station. The station is one of the busiest on the entire tube network, with over 50 million passengers in 2017 (another Jubilee Line station, Stratford is the busiest with 62 million). Foster + Partners also designed North Greenwich bus station connecting to the tube station by Alsop Lyall & Stormer. The bus station features a curving glass roof supported by tree-like steel columns, whilst the tube station forsakes the usual JLE palette of grey and silver for a striking use of blue throughout. Beyond the final three stations on the line (Canning Town, West Ham and Stratford) is Stratford Market Depot by Wilkinson Eyre, the main train depot for the line extension, featuring an arched roof 328 feet wide by 524 feet long. Despite the delay to opening and the cost running £1.5 billion over budget, in architectural terms the Jubilee Line Extension can be seen as a great success. The eleven stations, and attendant bus stations, ventilation shafts and depots form the most coherent London Underground project since Charles Holden’s Piccadilly Line extensions of the 1930’s. The use of the High Tech idiom, by architects such as Norman Foster and Michael Hopkins, has set a template for transport projects such as the also much delayed Crossrail project. As infrastructure projects grow more complicated, expensive and environmentally damaging to produce, we can look back on the Jubilee Line Extension as possibly one of the last great public combinations of form and function.

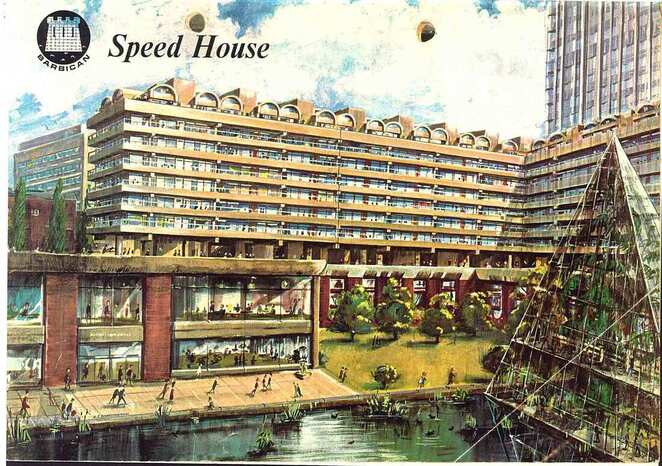

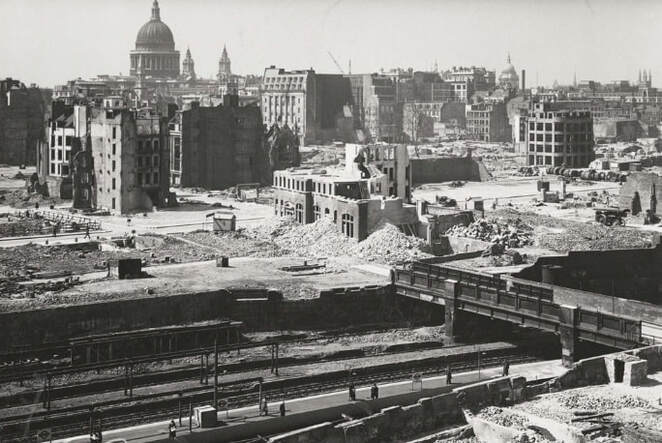

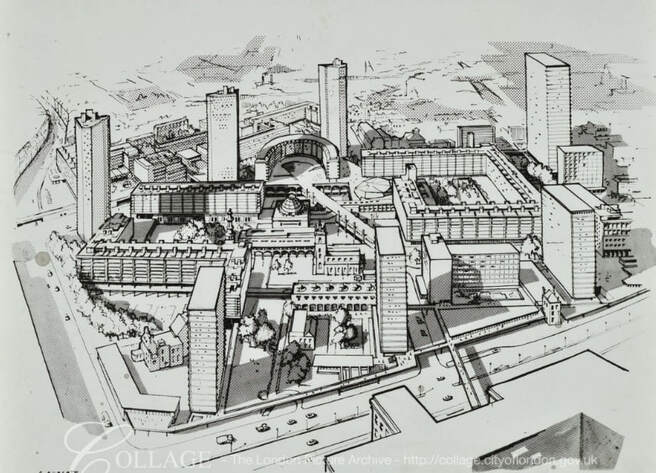

References The Jubilee Line Extension by Kenneth Powell The Barbican Estate welcomed its first residents in July 1969, with the completion of Speed House. The estate as a whole would not be completed until 1982 with the opening of the Barbican Arts Centre by Queen Elizabeth II, but it had been planned 20 years earlier. In the early 1960s the 35 acre site was a bomb site, having been hit by the Luftwaffe on 29 December 1940, destroying many houses, as well as the church of St Giles Cripplegate which now sits at the heart of the estate. Various plans to rebuild the area were put forward after the end of the war. The partnership of Peter Chamberlin, Geoffry Powell and Christopher Bon had designed the nearby Golden Lane estate for the City of London in 1951, and they were asked to produce a plan for the vacant site. Their initial plan for 5000 residents was expanded to the whole site, and they were asked to incorporate the City of London School, the City of London School for Girls and the Guildhall School of Music and Drama. Their new plan was debated and revised through planning committees before finally being approved in November 1959. Construction finally began in 1963, with the first residential blocks opening in 1969, and being completed in 1975. Ove Arup & Partners were brought in as structural engineers for the project. The dominant feature of the estate are the three towers; Cromwell, Lauderdale and Shakespeare. Each tower has three flats per floor, plus a penthouse flat, with each flat positioned in a corner of the triangular towers. The towers also feature striking projecting balconies which give the buildings their angular profile. Thirteen, terrace blocks of seven storeys take up much of the estate, many of them on podiums allowing circulation and light between different parts of the site. The flats in the terraces were designed to have flexible living space, with sliding doors used throughout. The estate also features two terraces of two storey houses and a row of townhouses.The concrete exterior of most of the buildings were bush hammered, giving the estate a monumental, weathered look. As important as the interiors and buildings, is the landscape design of the estate. The grounds feature gardens, trees, pools, water cascades, fountains and seating areas. As well as the residential parts of the estate are many other sections. Blake Tower was built as a YMCA centre and is situated between the Barbican and Golden Lane estates. It has now been turned into a residential tower. Elsewhere there is a library, the City of London School for Girls, the Guildhall Centre for Music and Drama, the Museum of London (designed by Powell and Moya) and the Barbican Arts Centre. Also within the site is the Highwalk, part of the post war system of elevated walkways built in the City of London. Initially conceived as a way of separating pedestrians from traffic, and allowing people to move all over the Square Mile, only a small part was built with much already demolished. However a few fragments still survive, and some are being extended. The estate is now home to around 4,000 people, and was Grade II listed in September 2001. Despite this listing and its recent popularity as brutalist architecture is reassessed, parts of the estate are under threat. The City of London School for Girls wants to expand their buildings, which would fill in one of the sub-podium spaces under Mountjoy House, destroying one of the estates many vistas, among other changes. You can read more about the expansion and sign a petition against HERE.

The Barbican is one of the great post war building projects in London and indeed Britain. It forms a great modernist village within the City of London, with its towers and terrace blocks overlooking the water features, arts centre and schools. Fifty years after the first residents moved in it has become a reminder of the ambitious and idealistic era of architecture. We hope that in 50 years time we will still be able to enjoy the vision of Chamberlin, Powell & Bon. As Nickolas Pevsner said “There is nothing quite like the Barbican in all of British architecture”. For a more detailed history and appreciation of the Barbican Estate, visit the Barbican Living website |

Archives

September 2022

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed