|

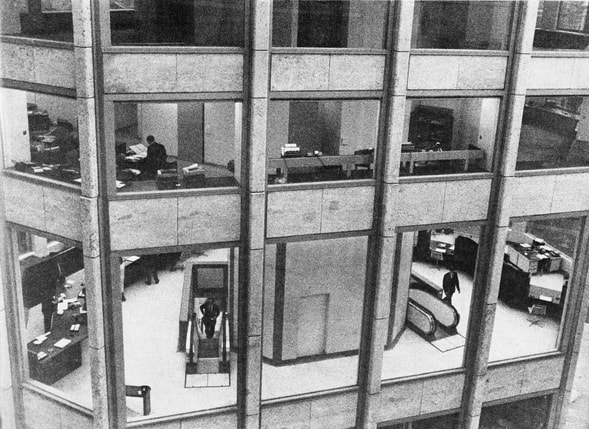

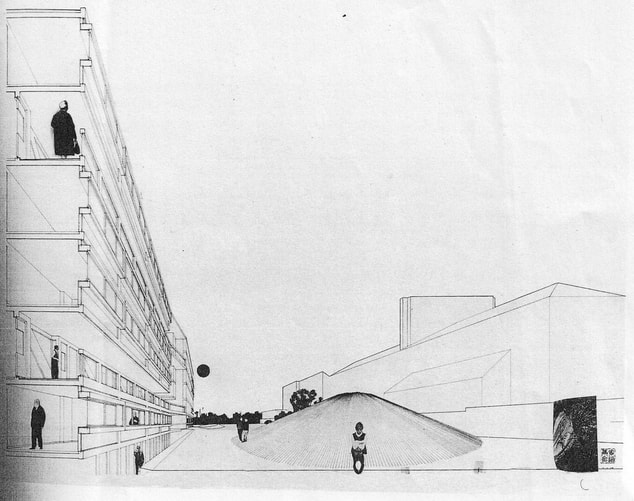

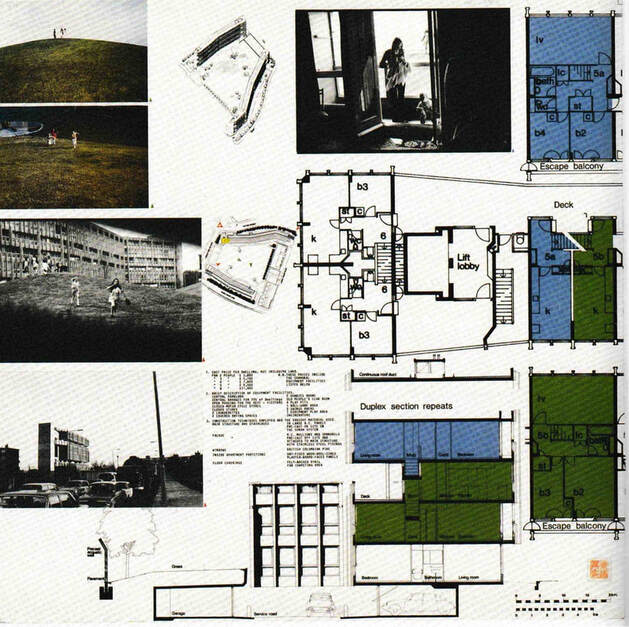

For 50 years the Robin Hood Gardens estate in Poplar has drawn praise, criticism, derision and scrutiny, much like its designers, Alison and Peter Smithson, did in their lifetime. As the last remnants of the estate are demolished we look back at how and why this divisive monument to modernism was built, and why it will soon vanish. The estate was commissioned by the Greater London Council, a prodigious builder of new housing since 1945, when it was the London County Council. The inhouse architects departments of these two organisations designed the lion's share of the capital's new estates, but outside architects were often commissioned to design municipal projects, most notably Erno Goldfinger whose Balfron Tower is just a stone's throw away from Robin Hood Gardens. The Smithsons came to fame with their design for Hunstanton School in Norfolk (1954), a pared down retort to the Scandinavian flavoured modernism of postwar British architecture. The next 15 years saw more column inches than completed projects, with their largest building being the Economist Offices (1965) in St James Street. The idea for an estate in the area had first been proposed in 1963 on what was then Manisty Street, home to the 19th century Grosvenor flats, built as part of previous slum clearance effort. The site was later expanded with Robin Hood Lane as its eastern boundary from which the estate would take its name. Over the next few years the site and brief were altered until a plan for 214 homes housing 700 people in two long slab blocks running parallel to the Blackwall Tunnel approach road were confirmed. In between these two slabs would be a green area, a ‘stress free’ area protected from the chaos of city life by buildings of the estate. In the middle of this area a mound was created using construction debris, creating a focal point for the space and a feature for the estate's children. An important part of the design of the estate were the block’s ‘streets in the air’, external access decks that the Smithsons hoped would become inhabited and used just like the terraces of neighbouring streets. This idea was first introduced by the Smithsons for their Golden Lane Estate competition entry in 1952, eventually won by Chamberlin, Powell & Bon. The depth of the walkways were to be sufficient so “Two women with prams can stop and talk without blocking the flow..”, and children would be able to play outside of their flats. Alongside the Smithsons, the recently deceased Christopher Woodward and Ken Baker helped design the project. The flats were arranged so the living areas and kitchen/dining rooms were largely facing away from the main road and towards the garden area. All flats, except for those for the elderly on the first floor, were on two levels with the bedroom placed either above or below the entrance floor. The exterior of the two blocks featured modulated concrete facades, another attempt to deflect noise from the busy parallel road. The Smithsons had approached the design of the estate in typically unconventional style. They researched the area's history back to the start of the 18th century, taking interest in the trades, residents and buildings that made up the neighbourhood. They also took brass rubbings of old street plaques, produced photomontages and even a mosaic made up of shards of china originally used as ballast by ships in the nearby docks. The materials used for the construction of the estate were unapologetically brutalist, with the blocks formed by a mixture of insitu and prefabricated concrete, overseen by engineering consultants Ove Arup & Partners. The systems part of the construction employed the Sundh slab method, developed by Swedish engineer Ernst Sundh, with the contractors Walter Lawrence & Son responsible for this and the construction of the whole site. The estate was completed at the point at which the tide started to go out for large, systems built concrete housing schemes. Architectural, social and financial opinion had turned against them in favour of smaller projects, largely made up of houses in brick with pitched roofs, as seen with the later Thamesmead phases. Vandalism was a problem from the start on the estate. The four outside play areas were damaged soon after opening and left unrepaired. The Smithsons were slightly bewildered at this violence against their design, seeing it as a reaction against consumer society rather than their buildings. This violence was matched by the local authorities' indifference to the upkeep of the estate. As seen elsewhere, the estate and its buildings were left to deteriorate until deemed not fit for use. Tower Hamlets drew up plans to demolish Robin Hood Gardens in 2008, as part of the regeneration of the Blackwall Reach area. Preservation campaigners and architects condemned the plans and launched a campaign to save it. Listing was turned down by English Heritage and a Certificate of Immunity was issued, barring any listing for 5 years. Another attempt at listing was made after this time had elapsed but was again turned down. The block on the western side of the site was demolished in 2017. The Victoria and Albert Museum salvaged a three storey section and other parts of the estate, but they have not yet been put on display. The remaining parts of the estate were cleared in 2022, the end to 50 years of Robin Hood Gardens. References

Alison and Peter Smithson (Works and Projects)- Marco Vidotto Alison and Peter Smithson (Twentieth Century Architects)- Mark Crinson Buildings of England: London East

0 Comments

|

Archives

September 2022

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed