|

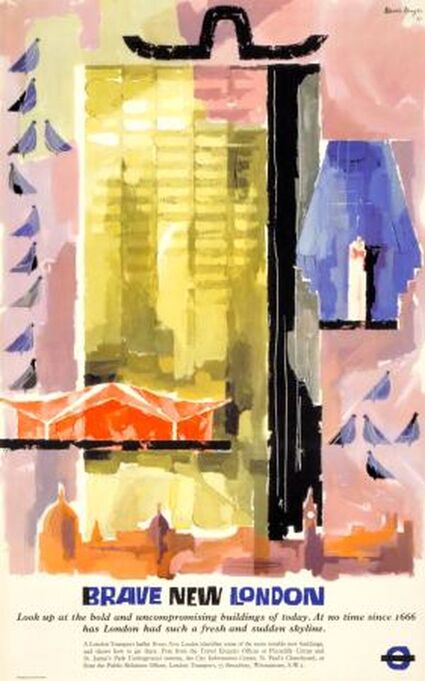

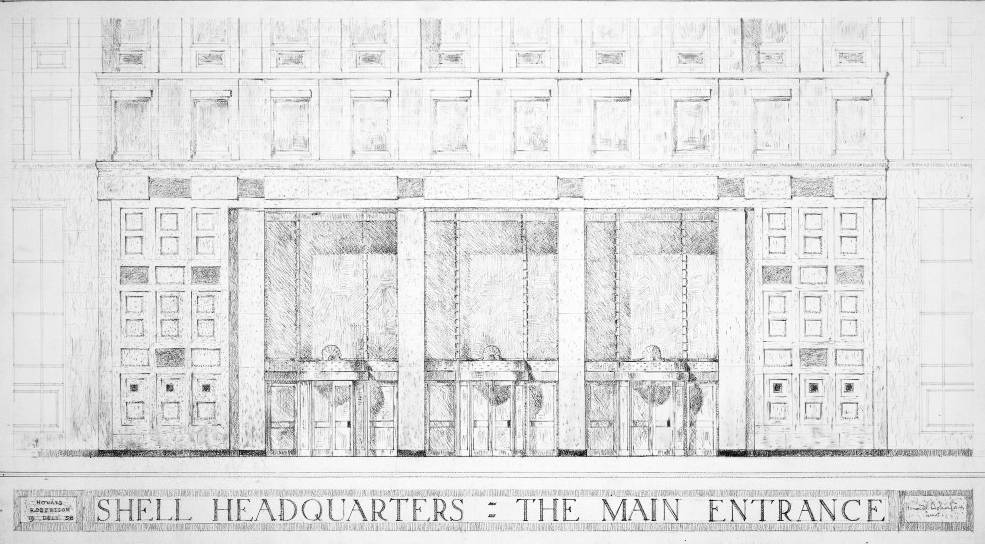

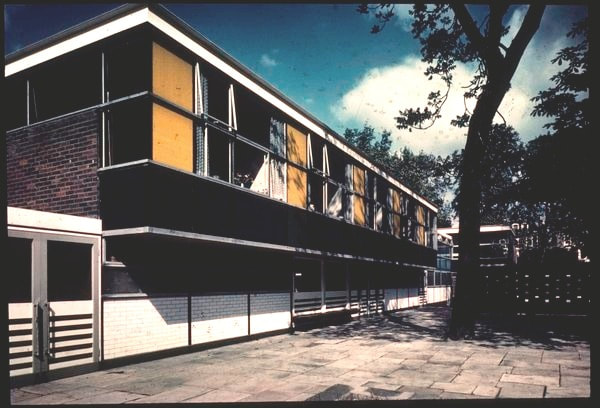

“Look up at the bold and uncompromising buildings of today. At no time since 1666 has London had such a fresh and sudden skyline” We have previously looked at the postwar rebuilding of Bethnal Green and White City, seeing how those areas rose from the literal ashes. We now turn to look at the centre of the capital and how the city remade itself into Brave New London. In 1960 London Transport issued a leaflet and poster highlighting the new architecture springing up across the capital. They were both designed by artist Hans Unger, who would later design some of the Victoria Line tilework, (read more on his life here). The leaflet listed a number of buildings recently completed across the city from the Alton Estate in the west to Span estates in Blackheath in the east. Of the 24 buildings listed in the leaflet, 5 have been demolished outright and a couple more have been refurbished. The remaining buildings are intact and largely listed. Some of the buildings featured are still considered classics of their time, whilst others have slipped into obscurity. We will examine all of them here. Starting with the demolished buildings, the two headliners are Owen Williams’ Daily Mirror building and the Peter Robinson store by Denys Lasdun. The Daily Mirror building at Holborn Circus was built between 1955-61, providing a new headquarters for the newspaper. It was the last building Willaims was involved with before retiring, with the firm of Anderson, Forster & Wilcox designing the exterior and interior finishes. The building was deemed surplus to requirement in 1994, when the paper moved to Canary Wharf and was demolished. The Peter Robinson building (1957-9) was a five storey department store on Strand, with an exterior palette of glass, stone and bronze. The ground and first floor were the sales floors, with the top three floors consisting of offices. The building was demolished in 1996. The other demolished buildings are; Bucklersbury House on Cannon Street by Owen Campbell-Jones offices demolished in 2010, Moor House on London Wall another office building, this time replaced by a Terry Farrell design, State House on High Holborn by Trehearne & Norman and Quintin School in St John’s Wood by Edward D. Mills & Partners, demolished in 2014 for a Van Heyningen and Haward design. The refurbished projects include Eastbourne Terrace (1958) in Paddington by C.H. Elsom & Partners, an office complex refurbished by Stiff & Trevillion in 2016. Thorn House on Upper St Martin’s Lane by Basil Spence has also been given a makeover. The 15 storey building was opened in 1959 for Thorn Electrical Industries and featured an eight foot high exterior sculpture by Geoffrey Clarke. The building was refurbished in 1990 by Renton Howard Wood Levin, the partnership founded by the building's original job architect for Spence, Andrew Renton. The remaining, existing buildings are largely housing estates with a few schools and offices included. The most famous schemes on the list are the Alton Estate in Roehampton and the Golden Lane Estate in the City, now both icons of early postwar modernism. Lesser heralded estates include Highbury Quadrant (LCC, 1954), Lansbury (L.C.C, 1951) Sceaux Gardens (1959) and Munster Square (Frederick Gibberd, 1951). Aside from Sceaux Gardens, designed by the architects department of Camberwell Metropolitan Borough Council in a typically Corbusian style, the other estates showcase a Scandinavian influence, which was more widespread in the early postwar period. This schism was laid bare at the aforementioned Alton Estate, when the two competing factions of the LCC housing department faced off across the slopes of Roehampton. The eastern section was designed by a team under Rosemary Stjernstedt in the Scandinavian idiom, with the western sector designed in what would become the dominant New Brutalist style of the 1960s. This team for this section was made up by the future founders of Howell Killick Partridge & Amis, as well as Roy Stout later of Stout & Litchfield. Two Span estates are also included on the list, Parkleys (1956) at Ham Common and The Hall and Corner Green (1957-9) in Blackheath. Span Developments was founded by Geoffrey Townsend in 1956 to create speculative, modern estates influenced by Scandinavian design. Houses were usually flat roofed, two storeys high and arranged in terraces. Apartment buildings were usually no more than four storeys with open plan interiors. The company's estates, designed by Eric Lyons & Partners, became very popular with new schemes being built all over London’s suburbs and the Home Counties. Parkleys is one of the best known of Span’s estates, with the housing spread around mature trees and hedges, allowing the estate to flow and be part of its neighbourhood. Another Lyons project featured in Brave New London was his housing for the Soviet Trade Delegation in Highgate (1957), which includes a four storey apartment block in exposed concrete and brick with a nursery and an assembly hall. Away from housing there are four office blocks in the guide. Congress House on Great Russell St was designed by David du Reiu Aberdeen for the Trade Union Congress, opening in 1957. Aberdeen had won the competition for the building in 1948 with his design featuring large areas of glass on the ground floor, a granite and blue tile exterior and an inner courtyard with a war memorial by Jacob Epstein. The building was refurbished between 1996 and 2019 by Hugh Broughton Architects, upgrading facilities and restoring original materials. Castrol House on the Marylebone Road (now Marathon House) was completed in 1959 as offices for the oil company. It was designed by Gollins Melvin Ward & Partners, and was one of the first American style post war skyscrapers in the country. The building is arranged in the slab and podium manner, with a 16 storey tower next to a lower podium block, and a glass curtain wall finish. The building has now been converted to apartments with the curtain walling curtailed to allow domestic occupation. The other two commercial buildings are the Sandersons offices and showrooms and the Shell Building on the South Bank. Sanderson House (1960) in Berners Street was designed by Reginald Uren of Slater, Moberley and Uren, with a glass curtain wall as at Castrol House and a courtyard garden. The building's most interesting feature is the stained glass panels by John Piper. Sanderson House was listed in 1991 and turned into a hotel in 2001. The Shell Building (1960) was designed by Howard Robertson as headquarters for the Shell oil corporation. It was built on the site of the recently cleared Festival of Britain and was criticised for its dull design, being finished in Portland stone rather than concrete or glass. The building was arranged in two sections, an “Upstream” building and a “Downstream” building. The upstream building was a 27 storey tower with adjoining 9 storey wings (the wings have been demolished). The downstream building, separated from the tower by the railway, is a 10 storey L-shaped block with a curved range, now converted into apartments. The last couple of buildings on the list are designed for the younger generation of the time. Bousfield School (1956) in Chelsea was designed by the partnership of Chamberlin, Powell & Bon, known for the designs of Golden Lane and Barbican estates. The school features curtain walling with coloured panels and a spherical concrete water tower in the grounds. Holland Park School was designed by D. Rogers Stark of the LCC, to house 2000 pupils on a site that was formerly part of the Georgian era Phillimore estate. The school buildings were arranged in long ranges of four storeys, built in dark brick with glazed stair towers. The 1950s building was demolished at the start of this century, with a new school building opened in 2012. Holland Park Youth Hostel is included along with the school. The hostel was opened in 1959, designed by Hugh Casson and Neville Conder on the site of Holland Park house, partially destroyed by Luftwaffe bombing. The final building on the list is Gardiner’s Corner, which seems to have been a department store at the junctions of Chapel Street and Edgware Road, probably where the current Tigris House is. The leaflet showcases a rising new metropolis, with bombsites and grimy Victorian buildings supplanted by high rise structures of concrete, steel and glass. Of course this transformation did not meet with universal acclaim, with many observers worrying that Old London would be replaced by mini Manhattan. The London Transport Board would continue to boast of the capital's new architecture with the publication of Modern Buildings in London by Ian Nairn in 1964, a slim but thorough roundup of modernist buildings on the extended transport network from the 1930s to the mid 1960s. As we have seen, much of what is “Brave New”, quickly becomes “Feeble Old” and disappears for something more up to date. But in buildings like the Alton Estate, Golden Lane, Bousfield School and others we can still see a glimpse of the future as seen from 1960.

0 Comments

|

Archives

September 2022

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed